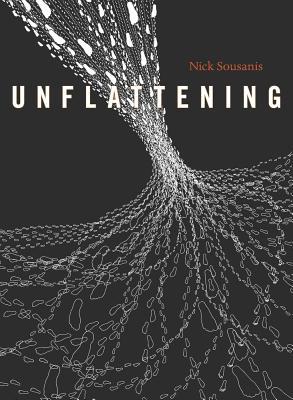

"Unflattening" is an

experiment in visual thinking. A scholarly discourse through the form of comics. Very possibly, the only one ever produced so far.

The

author, Nick Sousanis, earned his Ph.D. in interdisciplinary studies

last year from Teachers College Columbia University, where he produced

his dissertation entirely in comics form.

Harvard University

Press decided to publish the dissertation as a book, the first time the

press has printed a comic. This fact - in itself - can explain why, unfortunately, the content of

the book is not as exciting as the concept itself of "writing a PhD

dissertation using comics". It's just not as strong and stimulating as it could have been.

The drawings are beautiful, inventive, and the author's love for comics is palpable all through this book.

Overall, Sousanis argues in defense

of multiple perspectives on reality and the power of visual literacy:

"

For centuries, words have been considered the superior currency of

intellect. So much so that our reliance on the written word, like any

other kind of

dominant perspective, is so pervasive that we don’t even

realize our role in perpetuating it", he argues.

The question he fails to answer is the following: is

this really a dominant perspective that we all follow sheepishly, or

is it rather an evolutionary achievement driven by the need to

find the most effective, practical and articulate mean of communication?

But

beyond that point, this argument seems to ignore that a big

part of the Western world has already evolved, or it is moving on from

the limitations of the written word, by embracing a kaleidoscopic mix of words and

images. Snapchat. Emojis. Memes. Most young people use their mobile devices more than they read books.

Or look at the Kahn academy, at all the new approaches to teaching, the

youtube-spin-off educational tools, and any type of internet-based

graphic-related serious study.

So here is the

first

issue with this work: the fundamental concept doesn't seem to be that solid to start with. Within the academic world, the concept of a

dissertation in comics might be extravagant and very exciting (not "oo-hoo! Party!" exciting, but you know, university exciting) , because here is a comic

about a serious research work being made of comics instead of words.

But outside of the academic

world?

Ok, let's agree with the author's postulate: a university dissertation should not necessarily and

strictly be a thing made only of words. That is a thing of the stuffy,

rigid past. Images, drawings and comics can be widely used to express

complex arguments of philosophy, science, religion, whatever else. Let's

agree with the author.

Unfortunately, though,

I really do not

see how anyone would care for a split second about this, given that academic language is a niche, an extremely limited area of interest.

Second issue: more importantly,

not a single one of the ideas presented in

the book is new or even slightly original.Third issue: the dissertation should have been better articulated, the concept

conveyed with stronger arguments. It's good that someone is thinking

about shaking things up a bit in the world of dissertations, but let's

not forget that this is still, ultimately, a doctoral dissertation, and

as such, one would expect much stronger and stimulating arguments.

Instead,

the grounds for the dissertation's arguments are actually pretty weak and

vague. Is it maybe my snobbish-European-who-studied-philosophy point of

view? I don't think so.

Sousanis doesn't go much further in his argument than stating that everything can be seen from different perspectives, and that

"people" (never contextualized, never specified who or where) see things

in a flat way, never stepping out of their habitual way of thinking,

and doing things "just because they've always been done this way".

I

kid you not,

the author hammers on this simplistic common-sense concept for more

than two thirds of the book, using different metaphors and examples to

repeat the same concept over and over.

Even worse, these metaphors

are conveyed through negative, bleak, pessimistic drawings, as if

this lack of out-of-the-box, ever-evolving imagination was a social

disease instead of an absolutely normal aspect of being human.

The

main practical problem of this view is that

keeping a steady point of

view, albeit rigid and illusory, is a very healthy thing that a human

being can do. People who question their assumptions less than others

live more comfortable lives, this is just a fact. Evolution, in its millennial wisdom,

has set things up so that only a few people need to make the effort to

look beyond the limits of their usual point of view, and provide new

ideas, inspiration, new points of view. Not the majority. Because being

like that is painful. It's generally the outliers who come up with the

best ideas. But here is the thing: either you are, or you are not. A

book, in prose or graphic novel format, is not going to change anything

at all.

So why argue this point? Just to make an over-long

introduction to the real point, which is "comics can communicate as well

as words or even better sometimes, even in dissertations like this

one?"

What is surprising is that this real point is very thinly

argued. The argument, I gather, is supposed to be the book itself. However,

trying to prove that using different points of view is a good thing is hardly the

most cogent and specific proof that using comics in a doctoral

dissertation can be useful. That is too broad, too weak, just not enough.

Yes,

there is also a good section about the value of drawings and comics in

general, but there are many other arguments that the author could have

explored and he left out. Facts, proof that in different world cultures

the value of images vs. words changes, and that in many cultures visual

literacy was/is higher than in ours, with successful results.

What

about the power of ideograms? What about the neurobiology of word-based vs. image-based language? Only

one time the book touches on something useful to his

argument, that the author should have expanded on, that is the

presence of visual literacy and visual communication in other cultures

(i.e. Pacific Islanders maps). Had he found more examples of that, he

could have made his argument a little stronger, but no, the book ends a

few pages later, offering yet another couple of metaphors about, again,

how we need to shift our points of view!

So in the end,

ironically, this book

seems to prove that the comics form, although very powerful, is not as

good as the literary form as a mean to convey arguments and to write a

scholarly dissertation. If we base our conclusion on "Unflattening", this is certainly true. However, I don't think that is the case. Images can say more than words, if handled with the proper intellectual strength and wisdom.

Finally,

a note about page 14: here we find a hugely misguided "good old days" narrative

that goes: "

This creature [man], who once [again, when?? In Da Vinci's times?]

attempted to define the universe through its own proportions, now finds

itself confined, boxed into bubbles of its own making.... What had first

opened its eyes wide, darting, dancing, has now become shuttered, its

vision narrowed". In other words: we used to be able to think with an

open mind, look for example at Humanism, but now we are not anymore, and

everything is shit because of that. Oh Lord... I'm sorry but this

one is so lame. Do you realize that not even 1.5 % of the European

population studied or cared about philosophy in Da Vinci's times? By

quoting Da Vinci, you are actually proving the opposite point, that it

has always been the outliers who brought truly original thinking. In

every age, there have been people thinking in a uniform

lazy-standardized way, and a few people who thought in new, original

ways. There wasn't a golden time when "people used to be all so

open-minded". There just wasn't. That is an academic abstraction.