What a splendid thing

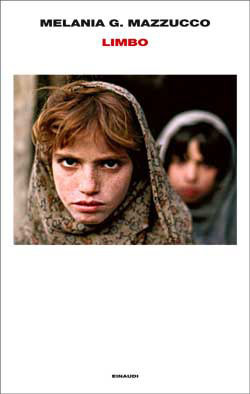

this book is. Inside and outside. Full disclosure: as an experiment, I bought this book

ONLY because I loved its cover. I didn't read anything about the content

or the author, I carefully avoided reading the cover blurb, and jumped

into it in complete ignorance.

What a splendid thing

this book is. Inside and outside. Full disclosure: as an experiment, I bought this book

ONLY because I loved its cover. I didn't read anything about the content

or the author, I carefully avoided reading the cover blurb, and jumped

into it in complete ignorance. I have a very visual imagination and I've loved many book covers before, but I've never bought a book just because of its cover, this was the very first time for me. A complete gamble. And I'm glad it paid off so well!

So, just for a second, take a look at this cover. Not only its intricately crafted stained glass drawing is very beautiful in itself, it also:

1). succeeds in evoking a certain complexity in the plot / content, therefore attracting thinking readers;

2). it works wonders on a tablet or computer screen: the back-lit surface of your device screen will give this cover an even more credible "transparent glass" effect. This cover, in summary, is just a marvel to look at. It deservedly won the BSFA award for "best SF book cover".

Adam Roberts loves Science Fiction. In a brief TED talk, he said: "Science Fiction is not similar to poetry, science fiction is poetry". So, no surprise there, Jack Glass is a Science Fiction book. In the author’s own words, the novel is a collision of ‘the conventions of ‘Golden Age’ Science Fiction and ‘Golden Age’ detective fiction, with the emphasis more on the latter.

The book is divided in three stories, all connected and all taking place in the same world.

From the start, we know from the narrator that the murderer in each story is Jack Glass, but that's all we know. The mystery lies in Jack's true identity, and in why and how he committed these murders.

The first story blew my mind. It was actually reminiscing of some Golden Age SF. Big Ideas SF. It's dark, intense, full of ideas and horrific, heavy moments.

With the second story the writing's tone shifts completely (maybe a bit too much?), introducing new important characters and, finally, providing a big picture overview of the universe where these stories are taking place. In a sense, you can see the first story almost as a prologue to the book. With the second story, Roberts is much heavier on the detective fiction. Yes we are still in a distant future, but it really feels like reading an Agatha Christie or Arthur C. Doyle story. And that is a good, fun, exciting thing. You can certainly feel the playfulness and the joy that Roberts was feeling while writing this book.

One could say that the main difference with a Sherlock Holmes story is that this one takes place in the future, and therefore it will be much easier for the author to come up with a clever resolution and make it seem oh-so-obvious, because he knows things about this world that the reader does not know. But I would counter that argument by noting that many of the Christie or Doyle stories, although firmly based in the present reality (of their author), used very similar deus-ex-machina devices to resolve everything at the end, and to make the reader feel like he had the obvious solution in front his eyes the whole time, and that he was a fool not to spot it.

The third story, "The impossible gun", sums everything up and brings us to a slightly deeper appreciation of Jack Glass as a complex character, and of his background.

Look, "Jack Glass" is just a load of intelligent fun. It's inspired by works from the Golden Age, but it's very original at the same time, and very well written. Does it lose a little bit of momentum at some points? Maybe it does, especially during the second and third story. Is it a bit too cold in its intricate plot? Again, maybe, but deep and involving character development is not the point of this book.

Maybe it's not a perfect book, but it deserves 4 stars and a half from me for the fun that I had reading it, and for the uncommon level of mental stimulation that it can generate.

SF author Paolo Bacigalupi wrote a very positive review of this book, wondering why an author of Adam Roberts' talent has not won any of the big SF awards yet (he did win the BASF award for Jack Glass though). And Bacigalupi finds his own answer in the fact that Roberts is a unique, very unconventional writer, who focuses on the Big Idea for each one of his books, and then moves on to something completely different. A serial experimenter. While it's much easier - and profitable - in these days, to strike gold with a more or less original concept, and then cash in on the series, and keep writing about the same characters. That might very well be true.